By Norman Bambridge

There has always been a great deal of mystery about the Battle of Benfleet and this is probably why, in spite of it’s importance, so few people have written about it. Indeed, from the time when the remains of the Danish great army left the island on the River Colne in Buckinghamshire, up to the day the fortified camp at Benfleet was destroyed, we have little written information to go on except the account in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

The version which contains the account was written by Ethelweard, great grandson of King Alfred’s brother Ethelred, some seventy years after the event, but it is generally accepted as true.

Beyond this, we have to rely on what the historians call “intelligent conjecture” that is, on deduction based on what we know about the state of affairs at the time.

We do, however, know enough to enable us to draw conclusions which are not far from the truth.

First, we know a great deal about the condition of the rival armies. The Danes had set out on a campaign hoping for plunder and eventually to conquer all of England, but by this time they had received a number of severe shocks.

They had not been able to join up their two armies in Kent; the main army had lost a battle at Farnham and had been driven headlong across the Thames and then surrounded by the Saxons under Edward and Ethelred.

Those who had got back to Benfleet were probably only a fraction of the original number, some of whom had been killed and others who deserted to join their friends elsewhere in the Danelaw.(1)

They would have reached Benfleet weary with fighting and marching, having lost most of their equipment and when they arrived at the fortification they could have found little to encourage them, for two further events happened. Haesten, in need of supplies, had taken off his force on a plundering expedition, leaving Benfleet manned by a garrison to guard the women and children, including his own.

The two hundred ships which had transported the great army from France had moved from Appledore to Benfleet but then left for a better haven in the waters around Mersea Island, leaving at Benfleet around eighty ships belonging to Haesten.

All through the campaign the English had done well, one victory being followed rapidly by another. The only real reverse was that of allowing the remnants of the Danish force to escape to Benfleet.

However, even this was not a strategic reverse, for the replacement within the English ranks of the men who had been campaigning hard for around six months, were replaced by fresh troops from the field-work and who were keen and ready to continue these battles.

Alfred himself had to go to the West Country, but had left behind two commanders, one being his son Edward, who was equal in ability to his father and he with his kinsman Ethelred of Mercia and the English army, gathered their strength in London and were joined there by a number of Londoners.

Some of them were merchants sons, others were from the English noble gentry and all were keen to meet the enemy. The morale of the English force was high, they were at the peak of their strength and fortunes, whilst the Danish survivors were the opposite in readiness.

London to Benfleet was a distance of little more than thirty miles. This is not a long way, but at that time, apart from the well trodden road through Ilford, Romford, Brentwood, Billericay and Wickford, the country was difficult to cross because of thick forest and extensive riverside marshland. This in itself, however, was rather to the good, for if the Benfleet fortification were to be taken, it would have to be by surprise attack.

One could not imagine the English army coming openly along the only road which at that time existed.

Ref: 1. Danelaw - Modern day counties included within the areas controlled by ‘Danelaw’ included areas of Derbyshire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Huntingdonshire, Leicestershire, Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex and Kent.

Alfred had already shown his mastery of guerrilla warfare when he had flung his forces into the heavily wooded gap in Kent between the two Danish armies. In Essex, his son Edward, had ample opportunity to show his own skill. There was good cover in the woods and in the desolate fens along the river Thames. It is true to say, the English would be crossing land which belonged to the Danes, but that meant little, for it was not in any way garrisoned by them. It had only been in the ‘Danelaw’ for thirteen years and the population was almost entirely Saxon who had sympathised with there fellow nationals and who could be relied on to keep secrets whilst these scattered bands were advancing under cover.

Thus sheltered and helped by the English “resistance” it is more likely the attackers were able to join forces on the high land around Hadleigh and Thundersley whilst the Danes, who appeared not to have ‘scouted’, were busy with their own affairs and who, in their encampment at Benfleet, may not have even known the enemy was ‘at hand.’ Once contact had been made, it is again possible that, before the Danes had time to recover from the surprise, their fortified camp could have been stormed, their ships taken or burned and their garrison captured, slain or driven out of the camp.

In trying to form some picture of what Benfleet was like at that time, we are told it was the site of a ‘fortress.’ It has generally been assumed that the fort was a temporary one, constructed by Haesten about the time of his coming to England in 892, but this may not be correct. The Latin Chronicle of Matthew of Westminster in the year 1326 speaks of it as being “strengthened by deep and broad trenches” which implies something more than a temporary fort.

At the time of the battle, Haesten was about sixty years of age and nearing the end of his adventurous career. During the ten years before the Benfleet campaign he had lived mainly in France and his forces had wintered each year near the mouth of the river Loire. Haesten, however, did not always stay with his men and had left the camp in September 892, probably for England.

It is possible that, knowing France was becoming exhausted through plundering expeditions, he was turning his attentions to another country. He may, at that time already have picked out Benfleet as a future base of operations, for we are told that the campaign of 892, when both armies came to England, had been planned beforehand.

Indeed, Haesten may have started the construction of his Benfleet fortification as early as 883. It was certainly there for him to retire to in 893 and would be hard to conceive of it being built when his army was face to face with Alfred’s forces in the weald of Kent.

It is always possible to make mistakes, but one imagines Benfleet to have had some years before 893 contained a small Danish community and to have acted as a retreat and ‘repair shop’ dominated by the fort which Haesten had built. There was wood, there was water and everything else needed for such a purpose. The Hadleigh Ray isolating it from the Thames made it much easier to defend from attack by water.

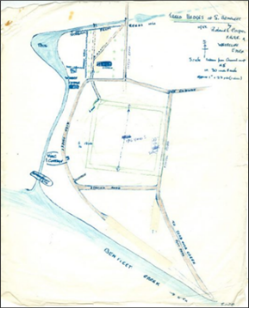

There cannot be much doubt about the position of the fort. The Danes being seafarers, had to find places for their strongholds where they could easily reach their ships. They preferred a spit of higher land almost surrounded by water if they could find one; but if not, they would protect themselves by digging ditches. The Danish camp at Castle Rough near Milton in Kent, though earlier than Haesten’s time, was of the former kind, while Haesten’s own camp at Milton was of the later, protected by ditches, a tidal marsh and long moat.

Benfleet had every advantage. The high spit of land was only accessible by the narrow Hadleigh Ray and was surrounded on all sides but one by water, for the creek in those days had not been silted up or shaped by the hand of man. It was much wider than it is now and the waterway would extend well up the valley beyond the church, below what is now Essex way. One authority has estimated that the arm of the creek where the roadway now passes over it could have been as much as twenty feet wide.

Even as late as the twentieth century there were ponds in this valley and those are clearly marked on the Tithe map of 1840 and on the six inch Ordnance Survey maps. Danish ships could enter the creek and smaller boats could penetrate well up the valley while at high tide the whole of the area now taken up by the railway and the low-lying fields would be an expanse of water.

In 1853 the Rev. A.E. Heygate, a local clergyman, wrote about the Danish fort in the transactions of the Essex Archaeological Society - “At South Benfleet when you alight from the train your eyes rest on a slight eminence immediately above the station and crowned by the parish schoolhouse, sloping gently towards the village gardens and orchards.

In A.D. 894 (893 probable) the scene was less peaceful and assuring than that which welcomes you now. That hill was a Danish fort and over the earthen wall which encircled it the double battleaxe gleamed with the red shields of those who were on guard, whilst their comrades were foraging or rather ravaging the district around.

The creek at the base, much wider and deeper was crowned with ships whose gilded serpents at the stern and gay figureheads at the bow, were too familiar to the Saxons in their admiration and cur. The station to which the Rev. Heygate refers is the old station further along the line than the one now existing. Its remains may still be seen.

The school house stood in the present School Lane almost opposite the place where the Church Hall stands today.

It is generally agreed that this was the area on which the Danish fort stood, but where were the ramparts and ditch which protected it on its fourth or eastern side?

It is believed that these ran along the line now traced by Grosvenor Road, then across St. Mary’s Road at the top of the hill and down the southern side of the incline to the Ray.

This seems probable for as we stand in St. Mary’s Road which runs along the ridge, we see quite a slope on two sides where the top of Grosvenor Road meets it. That on the western or fort side is steeper. Could this be the last trace of the fortification made by the Danes?

One may be mistaken, but on an aerial survey there appears to be a distinct line continuing as a kind of crop mark from the top of Grosvenor Road down the slope to the Ray, just beyond the point where the modern Ferry Road turns right to cross the bridge to Canvey Island.

The six inch Ordnance Survey map shows a field boundary along this line.

Imagine then, this whole area enclosed, on the water side by a strong stockade and on the landward side by ditch, rampart and stockade and this gives some idea as to what the fort would have been like. The Rev. Heygate mentions that in his day there was indentation on the west side of the hill which might have been at one time the last trace of an earthen wall, probably belonging to some interior castle or keep - a final defence point housing the chief of the garrison, its chief personalites and the bodyguard.

Another author writng in 1885 says that there were in his day quite enough traces around the churchyard to mark out one corner of the Danish fortress. Much has happened since those times to cover up those traces. It is possible that in the years 892 and 893 Benfleet had more people living there than in any other time up to the twentieth century. There must have been many huts in other parts of the two valleys and on the hillsides where woodcutters felled trees, carpenters trimmed planks and spars and the sound of hammer rang on anvil. even womenfolk are mentioned in chronicle saying that some were taken captive at the same time as Haesten’s wife and sons.

“The fortress at Beamfleote had ere this been constructed by Haesten and he was at the same time gone out to plunder and the great army was therein. Then they came thereto and put the army to flight and stormed the fortress and took all that was within it as well as the women and children also and brought the whole to London and Mancester (Bradwell) and they brought the wife of Haesten and his two sons to the King.”

In 1855 when the London, Tilbury and Southend railway line was being constructed, the navvies were driving piles for the bridge and preparing the track when they unearthed a remarkable discovery. Here they came upon fragments of ship’s timbers, charred black with fire. They had laid buried for almost a thousand years and about them lay quantities of

human bones - the remains of those who fell in the assault.

How did Edward and his brother-in-law storm this fort? Was it by direct frontal attack across the narrowing creek near the foot of the present Essex Way, or was it the same kind of bold action as that of General Wolfe at Quebec, a stealthy progress and gathering of forces by night on higher land on the downs?

It is unlikely that the Danes came out of their stronghold to fight on level ground for only the levels near at hand were flooded twice a day by the tide. The fort was certainly stormed but we don't know enough about the conditions on the ground, its vegetation and habitation patterns besides the numbers and preparedness of the two contending forces in order to make a guess. The truth about this mysterious battle may never be fully known though many legends have grown up around it.

One of these concerns a fragment of skin long believed to be that of a Dane found beneath the stud nails of the church door. This kind of story is not uncommon in Essex. At Copford, even in the twentieth century, a piece of material very much like thick leather was to be seen nailed to the church door and this too was believed to be the skin of some Dane who had been flayed alive for sacrilege. In Elizabethan days churchwardens gave a shilling for every badger caught and killed and the skins were often nailed to church doors as evidence that the vermin had been destroyed. This custom may have something to do with the legend.

Alfred was a humane and merciful king. When he received the wife and two sons of Haesten after their capture, he accepted them as friends because the boys were godsons of himself and of his son-in-law Ethelred he returned them with their mother to Haesten.

It is said that Haesten, overwhelmed by Alfred’s greatness of heart, swore he would never molest England again.

The Danes who survived the slaughter fled and set up another fortified camp at Shoebury and here the remnants of the great army gathered together. Shoebury being more distant did not present the same threat to London as Benfleet had done. Part of this camp site has disappeared under the sea but the outline of the other part remained into the twentieth century.

Nobody can describe the action at Benfleet as “great” in terms of the numbers engaged but like many other so-called minor battles, it was decisive because at the end of thirty years of war it marked “the beginning of the end” for the Danes. Alfred died five years later but the pressure on the enemy was kept up by his son Edward from London and by his son-in-law Ethelred from the west midlands.

In these wars Alfred’s daughter Ethelflaed, known as “the Lady of Mercia” took a leading part, showing great qualities of leadership. In time the Danian Boroughs in the Midlands were all taken, and after Ethelred and Ethelflaed died Edward continued to campaign and by 917 the Danes who still continued to fight had been confined to Essex.

Edward constructed a base at Witham and another fortified camp at Maldon. Four years later he drove them from their stronghold at Colchester although they replied by a5acking Maldon, they were driven off after a siege. After that battle, Edward repaired the fort at Colchester and thus became the ruler of the whole country. In time the Danes who remained in England settled down as farmers.

For more than fify years there was peace in the country under the wise rule of Alfred’s descendants and this peace was not broken until new forces of Danes under the formidable Sweyn descended on England.

The English King Ethelred the Redless (or Unrede - the King who would not listen to good advice) could not face them.

In about 884 she joined her husband in resisting the invasions of the Vikings. Ethelred was killed in battle against the Vikings in 911, whereupon Aethelflaed, after the Battle of Tettenhall, a great victory over the Vikings, became the effective ruler of Mercia the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle styles her as the 'Lady of the Mercians' (Myrcna hlæfdige).

Aethelflaed built the new Saxon 'burh' of Chester. Bonewaldesthorne's Tower, on the Chester city walls, is rumoured to have been so named after an officer in her army. She rebuilt Chester's walls in around 907 A.D. extending them to the edge of the river on the South and Western sides of the old Roman fortress, to establish Chester at the centre of a line of burghs, stretching from Rhuddlan in North Wales to Manchester, to protect the northern frontier of Mercia.

Her brother, Edward the Elder, born in around 868, succeeded their father in 924 and Aethelflaed allied herself her brother against the Vikings. She fostered

Edward's son, Athelstan and worked towards his eventually gaining the English

crown. Æthelflæd founded Tamworth Castle, as a burh to defend against the

Vikings, a statue dedicated to her, with her young nephew, Athelstan, dating to

1913 - and the 1,000th anniversary of the founding of the castle stands outside.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records:- '913: Here, God granting, Ethelflaed Lady of the Mercians fared with all the Mercians to Tamworth and there built the fortress early in the summer and after this, before Lammas, the one at Stafford'.

Tamworth served as a residence of the Mercian kings, to which Edward took his mistress Egwynna, His two eldest illegitimate children were born there, probably his daughter first, who remained unnamed in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, and then his eldest son Aethelstan, who was a great favourite of his grandfather, Alfred the Great, who ennobled him and presented him with a mantle of royal purple, a girdle set with precious stones and a Saxon seax (sword) in a golden scabbard.

Ethelfleda brought up her nephew and his sister at Tamworth. She feared her brother Edward, whom she was not always on the best of terms, would soon marry and Athelstan would be placed in danger if more sons were born to Edward. Fears that later materialised when Aethelstan was left out of the succession, and unsuccessful attempts were made on his life. Æthelflæd worked towards her nephew gaining the crown, who was eventually recognised as King of England.

She captured Derby from the Vikings and defeated them at Leicester. She had received an agreement from the citizens of York to take the city and was on her way to York but died suddenly at Tamworth in 918 before the campaign was completed.

She was buried beside her husband, Ethelred, at St Peter's Church (now St Oswald's priory) in Gloucester alongside the bones of St. Oswald a former Christian king of Northumbria. Her tombstone is now displayed in Gloucester City Museum.

In 991 Essex saw another battle when the English Ealdorman (or Earl) Brithtnoth met the Danes at Maldon.

Challenged to a fight on equal terms he allowed them to cross from Northey Island to the mainland and here the defeated and slew him. The Battle of Maldon is the subject of one of our earliest English poems.

In 1016 another decisive battle was fought at Ashingdon between Ethelred’s son Edmund (known as Edmund Ironside) and Canute (Knut), son of Sweyn. Canute had been making a raid deep into the eastern counties and was returning towards the River Crouch where his ships were anchored when Edward caught up with him, forcing him to turn and fight on the level ground between Ashingdon and Canewdon.

The English might well have won this hard-fought battle had not Edmund’s own brother-in-law Edric Streona fled at the second charge and brought ruin on his own countrymen. here has been much dispute about the site of this battle and though it is not strictly part of this story, most people think it was fought in this area and therefore must be made of it.

Edmund survived the defeat and agreed to share England with Canute, with Edward taking much of Wessex and Canute the rest of the country. however, Edmund died and Canute became the first Danish King of England.

Notes:

1086 A.D.

666 A.D. Probable date of the foundation of Barking Abbey

870 A.D. Barking Abbey destroyed by the Danes.

930 A.D.Probable date of the rebuilding of Barking Abbey

940 A.D. First mention of Thundersley in records.

991 A.D. Defeat of Brithtnoth at Maldon.

1000 A.D. Hadleigh mentioned as belonging to St. Paul’s.

1016 A.D. Battle of Ashingdon and Canute King of England.

1042 A.D. Accession of Edward the Confessor.

1066 A.D. Battle of Hastings.

1067 A.D. Death of Edward the Confessor. Accession of Harold and Battle of Stamford Bridge. South Benfleet Manor given to Westminster Abbey.

1086 A.D. The Domesday Survey began.

THE BATTLE OF MALDON

The following translations of the Old English poem are in existence:

-

Essex Review - Vol. 1929 by H.J. Rowles.

-

In the earliest English poems - by Michael Alexander (Penguin release)

-

In the Laurel Masterpieces of world literature - by Burton Raffell (Dell Publications)

-

Macmillan Papermac 1967 - by Kevin Crossley Holland and Bruce Mitchell.

It is worth mentioning that the first (1) is more literal or direct translation from the time whilst (2,3 and 4) are more clear and interpret the spirit of the poem.

Basildon Borough Heritage Society. October 2021.

Leave a Comment

I hope you enjoyed this post. If you would like to, please leave a comment below.